Given the recent announcement that congress may end funding for the Reconnecting Communities grant program, which funded planning and implementation of urban highway removals, I thought this would be a good time to talk about the benefits of such a program and how highway removals can transform our cities.

A few years ago I attended the “Re-Imaging Urban Highways” program in Philadelphia. Organized by Drexel University and The Next American City, the event was a who’s who of visionary planners at the top of their game discussing urban highway removals. The presentations focused on portions of the Interstate system that cut through cities and ways in which communities, planners, and local politicians can ameliorate the negative impacts of these highway segments.

The history of the Interstate System is long and involved, but I’ll provide a quick summary here. The core decisions which led to the Interstate being built through cities were made by the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, the highway lobby, and an array of other people at the state and local level in an effort to “renew” cities, sell cars, and move people as quickly as possible from their offices to suburban homes.

Highway promoters and builders envisioned the new interstate expressways as a means of clearing slum housing and blighted urban areas. These plans actually date to the late 1930s, but they were not fully implemented until the late 1950s and 1960s. Massive amounts of urban housing were destroyed in the process of building the urban sections of the interstate system.

By the 1960s, federal highway construction was demolishing 37,000 urban housing units each year; urban renewal and redevelopment programs were destroying an equal number of mostly-low-income housing units annually. The amount of disruption, a report of the U.S. House Committee on Public Works conceded in 1965, was astoundingly large. As planning scholar Alan A. Altshuler has noted, by the mid-1960s, when interstate construction was well underway, it was generally believed that the new highway system would “displace a million people from their homes before it [was] completed.”A large proportion of those dislocated were African Americans, and in most cities the expressways were routinely routed through black neighborhoods. Raymond A. Mohl, The Interstates and the Cities: Highways, Housing, and the Freeway Revolt

In the mid 20th century, traffic engineers viewed cities as traffic problems to be solved, and often times neighborhoods were destroyed in the name of moving traffic efficiently. As urban living and the reputation of cities have seen a resurgence during the last 20 years, these anachronistic viaducts have created more problems. Places like San Francisco, Portland, Providence, and Boston were left with blighted freeway ribbons through prime (sometimes waterfront) real estate. Robert Moses even wanted to run a highway through Lower Manhattan before it was stopped by Jane Jacobs, which would have destroyed some of the best urban neighborhoods and parks in the country. To paraphrase Peter Park, former Planning Director of Denver and Milwaukee and Loeb Fellow at Harvard: “We used billions of dollars of federal money to devalue some of the most valuable real estate in America.” It’s not just a real estate issue, either. California has issued warnings about building housing within 500 ft of freeways due to their known health impacts, which include increased risk of heart attacks, strokes, cancer, asthma, autism and dementia, according to the EPA.

As much as urban highway removal is about getting rid of polluting structures which divide neighborhoods, it’s also about economics. A comment made by the panel at “Re-Imaging Urban Highways” rang especially true: The land dedicated to urban freeways is an open faucet leaking money from the city. Instead of property tax revenue, new businesses and population growth, these highways consume land, depress land values, and give nothing back except a marginally shorter automobile trip for (usually non-resident) commuters. The commuters on the highway aren’t even spending money in the communities they drive through. Induced demand also means new or expanded highways create new traffic, quickly filling up lanes that were projected to be under-capacity decades into the future.

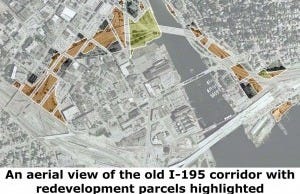

But getting rid of urban highways sometimes takes an act of god, or god-like political will and community mobilization. To paraphrase Thomas Deller, Director of Planning + Development, City of Providence, many state DOTs don’t care about cities – but they should. In Providence, where I-195 was torn down to create 20 acres of land which will be used to improve the social, economic and environmental health of the city core, requests by city officials for RIDOT to study highway removal alternatives were originally ignored. It took work by community groups which pushed the hand of the governor to demand that RIDOT study highway removal. Other removals, like the Embarcadero in San Franscisco, were catalyzed by earthquakes, while proposals like the I-95 Philadelphia highway cap are piggybacking off of regularly scheduled highway repair/rebuilds. If hundreds of millions of dollars are already being spent to repair infrastructure, why not make the city a better place for it?

Hearing about the successful highway removal in Providence reminded me of US 40 in West Baltimore and I-345 in Dallas. While working at Baltimore DOT in 2011, I managed a planning effort that studied capping a below-grade highway through low-income neighborhoods in West Baltimore. Parks and new development would be built on top of the highway cap. Recently, $85 million was allocated for the project, but that funding may now be in jeopardy given recent federal budget cuts. Likewise, a study by Texas DOT identified many of the deleterious issues associated with urban highways I’ve discussed here. The study proposed an array of design remedies for urban highways in Dallas, including tearing down I-345 in Downtown Dallas. If there’s some good that came out of urban highways, it’s that these structures serve as land banks which can spark imaginations and encourage planners and politicians to re-imagine what neighborhoods can be.

If you’d like a closer look at the real world results of urban highway removals, check out the Seattle Mobility Plan’s case studies for a rundown of projects all over the world. The Institute for Quality Communities at the University of Oklahoma also has before and after photos of urban highways. Finally, if you have an hour to spare, Congress for New Urbanism hosted a discussion about the traffic impacts of highway tear downs and how to sell these projects to politicians and the public.

Do you have a favorite urban highway you’d like to see repurposed, redesigned or removed in your city? Tell me about it in the comments below.

Highway 64/40 in STL is pretty iconic and I’d hate to remove it… but the 55 viaduct is such an absurdly textbook candidate for a cap-and-cover that it borders on stereotype.

In Halifax NS it took $120m in public money to remove the Cogswell Interchange a down town urban highway planners pushed through in the 1960s & demolished a community of 2600 buildings. Now Halifax and city Planners are pushing through corridors, up-zoning for towers along transit routes that also include car and bike lanes. Hundreds of buildings are being demolished, without requirements for affordable housing or public amenity in the new highrises whenever/if they're built. Historic buildings and 80 trees along Robie Street will be destroyed to add a second bus lane but maintain the lanes for cars. Unless we reallocate existing road space aren't corridors just a new form of urban highway?